Introduction to Public History, Chapters 1-4

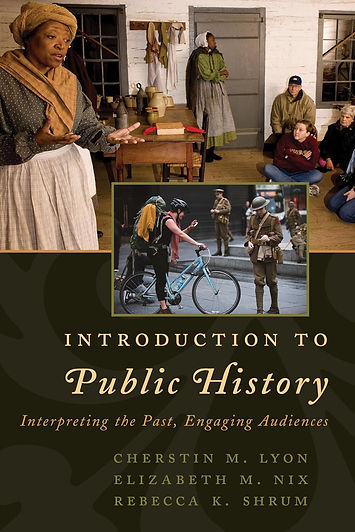

In Introduction to Public History: Interpreting the Past, Engaging Audiences, authors Lyon, Nix, and Shrum introduce those new to public history to key terms and concepts through case studies that encourage readers to think critically about the field.

One of the first concepts the authors introduce to the reader is collaboration with stakeholders. Public historians must think past the intended audience of a public history site and give thought to the diverse group that can have an interest or a stake in the work they do. Involving the stakeholders whose stories are being told is crucial. However, a public historian must be careful to tell the history based on sound historical evidence and not be over-influenced by stakeholders such as benefactors or politicians, who may not have any relationship to the histories being presented beyond their involvement with the organization. This thought on stakeholders puts me in mind of a conversation I had over the summer with the director of my local historical society in which she alluded to the careful balance she must maintain between the board of directors, the county commissioners, the volunteers, the society's staff, the audience, and the stories the organization wants to tell. While she is a field veteran, she never imagined that this part of the job would require such careful handling and attention. She advised me to be an excellent listener, communicator, and, at times, a master negotiator. The "Jack-of-all-trades" skill set needed to be a public historian, especially at a small organization with limited resources, is likely more diverse than most of us yet realize.

The second chapter is filled with valuable information to help navigate the historical methods used by historians. When reading about the concept of history as a practice, my mind immediately went to my experiences visiting Greenfield Village at The Henry Ford in Dearborn, Michigan. The way they use knowledgeable costumed interpreters that partake in day-to-day activities of the era they represent to connect visitors to the past and the histories of the buildings that make up the village is an excellent example of doing history. The interpreters don't just recite a script but invite visitors to engage with history by asking questions, thinking critically, and exploring the history surrounding them. While not perhaps suitable for all public history sites, this approach seems to resonate well with visitors of all ages.

Chapter three discusses the value of oral histories. Those who record their account of history from their own perspective become narrators who can contribute to a collective history. Public historians may find it challenging to convince people to tell their stories and that the stories are worth being recorded. Overcoming this barrier requires building a relationship of trust with interview candidates.

In the fourth chapter, Collecting History, "one of the fundamental realities of collecting is that it is impossible to hold on to everything." (Lyon et al., 2017) As someone with multiple personal collections, I find this statement holds so much truth yet is so painful, as I inherently think nearly everything is worth saving. However, the older I get, the more I find the need and value in curating my collections. I see parallels in how public history sites need to do the same, and I understand the why behind these decisions. As my own collection has grown, I have found that my interests have become more defined, and I only add an item to my collection if it fits specific criteria. My collections are also limited by space restrictions and the cost of acquiring new items. Public history sites face similar challenges, and why I do not parallel the significance of any of my collections to that of a collection under the care of a public history site, I understand the fundamentals of the curation process. As an organization grows and matures, it finds new areas that may align with its stakeholders' interests. They may run out of space or acquire more room to feature collections. Artifacts may no longer align with their mission or would be better suited for a different caretaker. A collection is ever-evolving, and a good public historian recognizes this and the challenges that come with it.

References

Lyon, C. M., Nix, E. M., & Shrum, R. K. (2017). Introduction to Public History: Interpreting the Past, Engaging Audiences. American Association for State and Local History.

Costumed interpreters in the Daggett Farmhouse at The Henry Ford's Greenfield Village in Dearborn, Michigan.